Vol. 10, No. 1• November 2005

Foster care placement disruption

in North Carolinaby John McMahon

By age 10, Amanda had joined 13 families.

She and three younger brothers entered the foster care system in 1992 because of parental neglect. By December 1999, Amanda had lived in 11 foster homes and had been removed from one adoptive family because of abuse. Combined with the removal from her birth parents’ home, Amanda had moved on average once every nine months for the first 10 years of her life.

Her brothers had fared little better. One had been in nine foster homes; the other two in eight.

— Indianapolis Star Editorial, Feb. 11, 2000

* * * * * * * * *

Though Amanda’s story takes place in the Midwest, we would be wrong to think that children do not have experiences like this in North Carolina. This article will outline what we know about foster care placement disruption and tell you what you can do about it.

Why Does Disruption Matter?

Before we begin it is important to acknowledge that moves for children in foster care are sometimes positive. If a placement is stable and yet failing to meet a child’s needs, agencies should make every attempt to meet that child’s needs within the context of that placement. If these attempts do not succeed, a move may be in the child’s best interests (Schofield, 2003).In general, however, foster care moves seem to do children more harm than good. The possible effects of placement disruption on child development are described below.

Impact Child Development?

There seems to be a link between foster care placement instability and poor developmental outcomes. However, we do not know enough yet to say whether children’s existing developmental delays contribute to multiple placements, whether these delays are a consequence of multiple placements, or some combination of the two (Harden, 2004).

When they ask her about the impact of placement changes on kids in care, Nancy Carter tells foster parents that they should think about it in the following terms:

For every move a young person makes in the substitute care system (including the first move from their biological family), assume they lose one year developmentally and academically. Therefore, a 17-year-old who has experienced 5 moves may respond emotionally and behaviorally much like a 12-year-old. They are able to catch up developmentally once they feel safe and secure in a placement with caring adults who provide experiences for them to grow self-sufficiently. Academically, every effort needs to be made to maintain a young person’s school placement.

Empirical data does not completely support this notion. For example, when researchers with the National Study of Child and Adolescent Well-being examined the well-being of 727 children who had been in foster care for more than 12 months, they found that children in care were behind in their cognitive and social development when compared with other children, but not to the extent Carter’s framework would suggest.

Carter’s framework may still be useful for you, however. Carter, a foster parent trainer and Executive Director of Independent Living Resources, says that her concept has helped many foster parents understand their children’s behavior. She says, “I have had foster parents come up to me after training and say they had planned to ask a social worker to move their teenager but after hearing this, they have decided to work with the teen a bit longer. That is a glorious moment! And this has happened more than once.”

Other ways in which children are affected by placement instability include:

Behavior. A large study of foster children found that the number of placements children had could be used to predict behavioral problems 17 months after they entered foster care. Other studies have linked placement instability to children’s aggression, coping difficulties, poor home adjustment, and low self-concept. Children may also experience behavioral difficulties if they think their placements won’t last (Harden, 2004).

Attachment. Attachment, the enduring emotional bond between a child and a primary caregiver, is key to healthy child development. Because of maltreatment and inconsistent or inadequate parenting practices in their families of origin, some children enter foster care with attachment problems.

Many experts believe that the experience of moving from placement to placement can also cause attachment difficulties or make existing ones worse. Indeed, in 1994 the American Psychiatric Association specifically cited “foster care drift” as a cause of reactive attachment disorder in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Long-term Outcomes. Pecora and colleagues (2005) recently examined outcomes for 659 young adults who had been placed in family foster care as children. They found that among these young adults:

- More than half had clinical levels of at least one mental health problem

- Only 2% had earned a BA or higher (compared to 24% in the general population)

- 20% were unemployed (compared to 5% for the general population)

- 33% had household incomes at or below the poverty level

- 33% had no health insurance

- 22% had been homeless at least one night

These researchers concluded that many of these negative outcomes could be eliminated or reduced by increasing the stability of foster care placements.

Is Disruption Common?

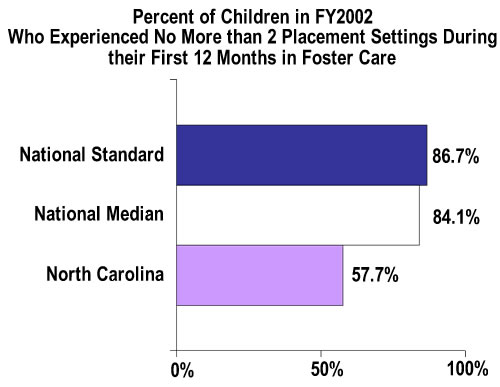

The longer a child remains in foster care, the more likely it is that he or she will experience multiple placements. For example, data indicate that between 33% and 66% of placements disrupt within the first two years (Harden, 2004). In fiscal year 2002, 73% of the children in the U.S. who were in care longer than four years had 3 or more placements (USDHHS, 2005).The federal government considers foster placements to be stable in a state if, of all children who have been in foster care for less than 12 months, 86.7% or more have had 2 or fewer placements. In FY 2002, most states achieved or came close to meeting this standard: the national mean was 84.1%.

In North Carolina, however, only 57.7% of children who had been in care 12 months or less had experienced 2 or fewer placements. This percentage is the second lowest in the U.S.

in North Carolina in 2002In a recently released federal report, North Carolina received low marks for the stability of its foster care placements. In our state in 2002, 42.3% of children had more than 2 placements during their first 12 months in foster care. This was the second highest rate of placement instability in the U.S.

Source: USDHHS 2005

What Contributes to Disruption?

System-Level Factors. According to an analysis by the National Resource Center for Foster Care and Permanency Planning (2004) the Child and Family Services Reviews (CFSRs), which the federal government used to evaluate the child welfare system in every state, identified the following as common obstacles to placement stability:

- Insufficient support for foster parents. The CFSRs frequently found child welfare agencies did not provide enough services to foster parents to prevent disruptions.

- Too few foster homes. The CFSRs found that in many states there is an inadequate number of foster homes, forcing child welfare agencies to make placement decisions based on what is available rather than on what is appropriate for the child. The result can be poor matches between child needs and caregiver strengths.

- Use of emergency shelters and temporary placements. The CFSRs noted that many states use these resources as initial placements and after a disruption occurs. Using them drives up the numbers of moves children must make.

- Lack of specialized placements. The CFSRs found a scarcity of appropriate placement options for children with developmental disabilities or behavioral problems. This leads to inappropriate placements and subsequent moves.

Foster Family Factors. According to Schofield (2003), foster parents say a placement is more likely to disrupt when:

- The foster parents dislike or reject the child

- Foster parents are concerned about the impact of the foster child on the rest of the family

- Stressful events occur in the life of the foster family prior to and/or during the placement

- Child welfare-related problems occur, such as allegations of maltreatment in the foster home or previous disruptions

Other Factors associated with placement stability include:

- Child age. The CFSRs found that placements for youth aged 13 to 15 were the least stable (NRCFCPP, 2004)

- Child traits. Children with severe emotional or behavioral problems are more likely to experience placement disruption

What Prevents Disruption?

Findings from the CFSRs suggest that foster care placements are more stable when (NRCFCPP, 2004):

- Children are placed with kin

- Children, parents, and foster parents receive more services

- Children and parents are involved in case planning

- Workers have more frequent contact with birth parents

Of course, the qualities of foster parents influence placement stability, too. In a study of placement stability in Illinios, caseworkers reported that children in stable foster placements received more attention, acceptance, affection, and overall better care from their foster parents. The skill and ability of foster parents to accept and manage oppositional/aggressive behavior was especially important.

Schofield suggests the following foster parent qualities also influence placement stability:

- Sensitivity towards the child

- Accepting the child for who he or she is

- Responding to the emotional age of the child

- Sensitive and proactive parenting around birth family issues and contact

- Active parenting regarding education, activities, life skills

- Boundaries: firm supervision yet promoting autonomy

- Enjoying a challenge!

What Can You Do?

As an individual foster parent there are some factors that contribute to placement disruption—such as the use of emergency shelters—over which you have no control. There are things you can do, however:Ask for help. Social workers report that adoptions sometimes disrupt because adoptive families wait too long before they seek help. Ask for help before you are past the breaking point.

Use respite. Respite care should not be reserved for emergencies. Respite allows foster parents to renew their energy, which can enhance the quality and the longevity of placements.

Learn. Research suggests that foster placements are more stable when foster parents have a clear and realistic understanding of the issues their children are struggling with, and when they have the knowledge and skills needed to successfully parent their children. In particular, foster parents should take steps to learn all they can about:

- Trauma and other mental health issues that affect children in foster care

- Their children’s right to receive mental health and educational services

- How to advocate effectively for these services

- Appropriate discipline techniques, especially for children struggling with trauma, mental health issues, and oppositional/aggressive behavior

Maintain family connections for the child. Sustaining connections between children and their siblings, friends, and other family members can add to their sense of stability.

Build and maintain your own support system. Keep strong connections to your family, friends, faith community, other foster parents—all the resources you need to stay healthy and keep fostering.

Position on Moving Children in Foster CareChildren are traumatized by separation and loss. Since children in the foster care system have already experienced trauma, special care must be taken by service providers not to compound it. The attachments children form with their parents and other caregivers should be recognized and respected.

Children in foster care often develop strong attachments to their foster parents; at times these are as strong as the bonds they have with their biological parents. The younger the child and the longer the placement, the greater the impact of moving that child from the foster parents to whom the child has become attached.

It is sometimes necessary to move a child because of imminent danger. However, moving a child from a successful foster care placement should be done only as a last resort, after support and services have been offered to the child and family to prevent the move. If a child must be moved, there should always be a transition plan for the child, developed with the child’s age and attachment needs in mind, as well as the depth of the child’s attachment to the foster parents and foster siblings.

(Source: www.nfpainc.org)

Click here to see the references for the sources cited in this issue of Fostering Perspectives.Copyright � 2005 Jordan Institute for Families