Vol. 17, No. 1 • November 2012

Overview: The TPR Process in North Carolina

Termination of parental rights (TPR) is the state's ultimate interference into the constitutionally protected parent-child relationship, severing all legal ties between the parent and the child. TPR may occur only if a court finds that grounds for termination exist and that TPR is in the child's best interest (Hatcher, Mason, & Rubin, 2011).

Although TPR does not occur for most families involved with the child welfare system, it does happen. On September 30, 2009, parental rights to 1,470 of NC children in foster care waiting to be adopted had been terminated (USDHHS, 2010).

Parental rights must be terminated or voluntarily relinquished before a child can be adopted. Because they are the group that most often adopts children from foster care, foster parents sometimes have a big stake in the TPR process. Of the 1,442 North Carolina children adopted from foster care in 2010-11, 66.4% were adopted by their foster parents (USDHHS, 2012).

Although they have may have an interest in the outcome, foster parents do not have a right to be notified or to participate in TPR hearings. However, as noted above, foster parents may be called as witnesses during TPR hearings, especially if they have done shared parenting or are willing to adopt.

The TPR Process

The following is adapted from Hatcher, Mason, & Rubin, 2011All TPR proceedings occur in juvenile court, before a district court judge without a jury. In North Carolina there are 10 reasons the court may terminate a parent's rights. A TPR proceeding is divided into two stages. At the adjudication stage, the party initiating the proceeding (often DSS) has to prove that one or more of those 10 reasons exists. If the judge agrees, the case proceeds to the disposition stage, in which the judge decides whether TPR is in the child's best interest.

If the court does not find that grounds for termination exist, or if the court finds that TPR is not in the child's best interest, the court dismisses the case. North Carolina courts considered terminating parental rights 1,889 times in 2009-10. Judges ruled not to terminate parental rights in 287 (15%) of these hearings (NCAOC, 2011).

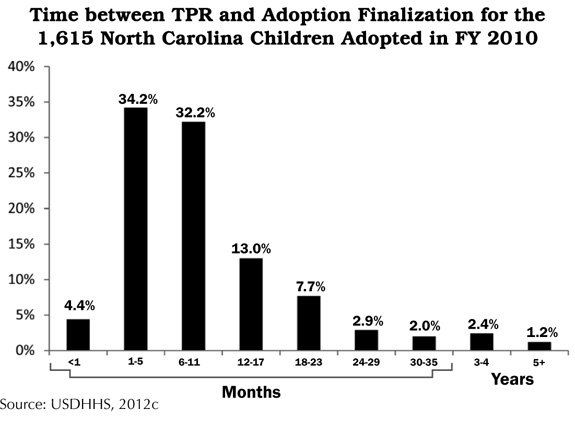

If the court terminates parental rights and the child is in the custody of DSS or a licensed child-placing agency, post-TPR review hearings are held at least every 6 months to examine progress toward achieving the child's permanent plan.

Appeals. Any order terminating parental rights or denying a petition or motion to terminate parental rights may be appealed. Appeals of TPR decisions are fairly common, though seldom successful.

Even if appeals of TPR are not successful, they can take a long time. Weathering this period of doubt and uncertainty can be frustrating and stressful for children and for foster parents, but as Destiny, winner of this issue's writing contest reminds us, it is worth the wait: "A judge's decision helped make me into the person I am today, with my mother and father--not the biological ones....That was the best decision that somebody could ever make for me."

To learn more, consult Chapter 9 of Abuse, Neglect, Depndency, and Termination of Parental Rights Proceedings in North Carolina by Hatcher, Mason, and Rubin (2011) online at http://sogpubs.unc.edu/electronicversions/pdfs/andtpr.pdf.

To view references cited in this and other articles in this issue, click here.

~ Family and Children's Resource Program, UNC-CH School of Social Work ~