Vol. 19, No. 1 • November 2014

We Can All Take Steps to Promote Permanence

First, let's be clear: if you are a foster parent or kinship care provider, you are already doing a lot to promote permanence for youth in foster care.

Yes, foster care is temporary. But it is not a limbo where nothing happens. Foster care can be a place that gives kids a chance to get their feet under them--developmentally, emotionally, cognitively, physically--while their families work to resolve their challenges.

The care and support you provide, the teaching and nurturing you do, the way that you understand and respond to children's behaviors--these things make a profound difference in children's lives, especially because they can make permanence easier to achieve.

Permanence

"Permanence" can have different meanings. When people use the word about children and youth in foster care, usually they are talking about legal permanence, which North Carolina child welfare policy defines as a lasting, nurturing, legally secure relationship with at least one adult that is characterized by mutual commitment."Legally secure" in this case means a placement in which the direct caregiver has the legal authority to make parental decisions on behalf of the child or youth (NCDSS, 2014a). Legal permanence is about reunification, adoption, guardianship, or assignment of legal custody. These are the types of arrangements the federal Adoption and Safe Families Act seeks to achieve by requiring states to conduct permanency hearings within a year after a child enters foster care.

There are two other important kinds of permanence we should keep in mind, however.

Relational permanency is the term for an emotional attachment between the youth and caregivers and other family members and kin (Univ. of Iowa School of Social Work, 2009, cited in NRCPFC. 2013). More and more, we are coming to realize that even when legal permanence isn't possible, relational permanence is.

North Carolina has made relational permanence one of the primary outcomes focused on by NC LINKS, our state's independent living program. For each teen in foster care we seek to build a personal support system of at least five caring adults in addition to the youth's relationships with professionals.

There's also cultural permanency, which is about maintaining a continuous connection to family, tradition, race, ethnicity, culture, language and religion (Univ. of Iowa School of Social Work, 2009, cited in NRCPFC. 2013). The importance of maintaining cultural ties is emphasized in the pre-service training foster parents receive and is supported by proactive, respectful communication with birth families and practices such as shared parenting.

Why Permanence Matters

These three forms of permanence--legal, relational, and cultural--have a big influence on young people's sense of self, their well-being, and the trajectory their lives. Though all are important, the effects of legal permanence have been studied most. Consider the findings of Courtney and colleagues (2011), who followed youth who had aged out of foster care and were 26 years old at the time of the study.Compared to their peers who did not spend time in foster care, these youth were:

- 10.5 times more likely to be incarcerated.

- 3 times less likely to have completed high school.

- 9 times less likely to have completed a 4-year degree.

- Nearly twice as likely to have a health condition or disability that limits their daily activity.

- Nearly twice as likely to be unemployed.

These and other negative outcomes experienced by young people who have aged out of foster care dramatically illustrate why legal permanence matters.

A Concerning Trend

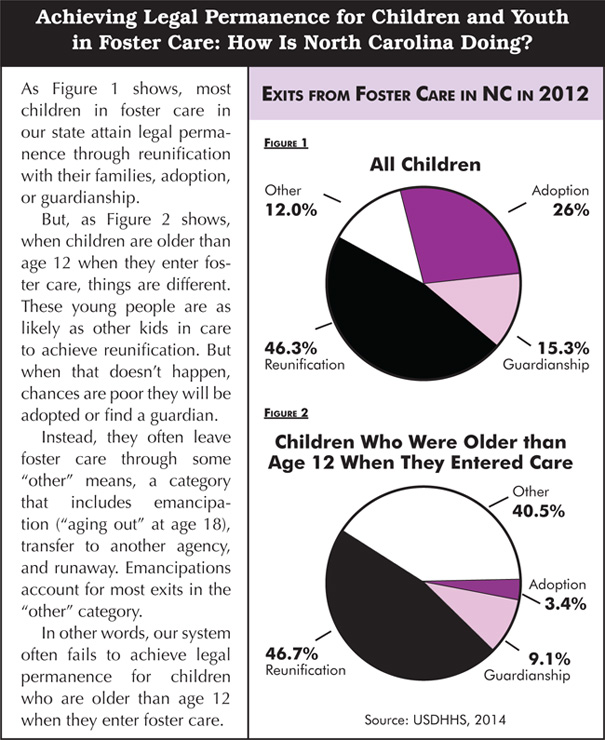

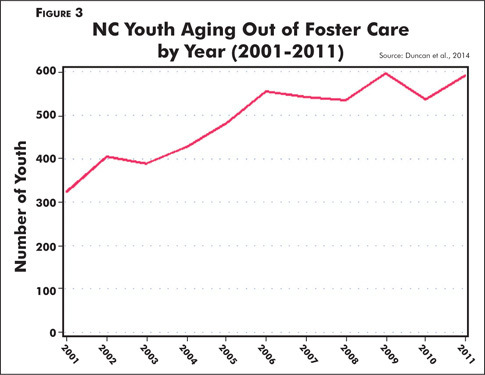

As the statistics on the previous page show, our system does not always do so well when it comes to achieving permanence for children--especially for those who are teens or tweens when they enter foster care.As Figure 3 shows, the number of youth aging out of care in NC without legal permanence has increased over the past decade. In 2013, 500 youth aged out of foster care in our state (Duncan, et al., 2014). In North Carolina a 12-year-old in foster care is 2.5 times less likely to be adopted, and a 17-year-old 9 times less likely to be adopted, than a 2-year-old (USDHHS, 2014).

Although adoption is not the only path, too many older youth are aging out without legal permanence of any kind.

What You Can Do

Many of the most significant barriers to achieving permanence for children in foster care are beyond the direct control of foster parents and kin caregivers. When it comes to overcoming these hurdles, most of the power lies in the hands of child welfare professionals, the court system, and children's families.However, there are things you can do to help. Following are some suggestions for steps you can take to promote permanence for older children in foster care.

1. Be open to fostering or adopting teens. Older youth in foster care are much more likely to live in group homes. While residential settings are the right place for some youth, many others live in group homes simply because there aren't enough foster families for teens. Consider opening your home to teens.

2. Offer to help recruit families for kids. Foster and adoptive parents are the most effective recruiters. Tell your agency you are willing to help spread the word!

3. Be willing to talk about permanence with young people in your home. Do this even if you can't be the forever family for the young person. It isn't easy, but kids need multiple opportunities to discuss their future and what permanence might look like for them. Social workers should lead these talks, but caregivers can also play a part.

4. Promote cultural and relational permanence. Do all you can to maintain strong connections to children's traditions, culture, language, and faith while they're in your care.

The same is true for connections to caring adults, even if these adults aren't in a position to adopt or be a guardian. If you know of adults who may be an ongoing support for the child, make sure the child's social worker knows so these connections can be kept maintained and encouraged.

5. Be an active part of the team serving the child. Know what the child's permanency plan is. Ask what you can do to help achieve this goal. Advocate for the youth.

6. Facilitate contact with parents, siblings, extended family, and other people important to the child. Visits are important, but so are other forms of contact--e.g., phone calls, letters, conversations via Skype or FaceTime, etc.

7. Practice Shared Parenting. Shared parenting creates a bridge between the two families. When the child returns home, lines of communication can sometimes remain open. In this way, you may still be able to be "family" for the child and the child's parents.

8. Use life books. Developing a coherent narrative of their lives and who has been important to them helps young people know and remember--on a deep level--important truths that make future success possible: that they are loved, capable, and connected.

9. Know about and, if appropriate, support other strategies described in this issue. These include:

- CARS agreements. Talk with your child about the option of CARS if there is even a slight chance they may not find permanence before age 18. If your county doesn't offer the CARS, advocate for a change.

- Permanency-related strategies, especially Family Finding and Child-Specific Recruitment, which are part of NC's Permanency Innovation Initiative.

- CFTs. Child and Family Team Meetings can be an ideal place to help youth explore lasting, nurturing relationships with adults who are committed to them and their success.

- Adult adoption. Formalizing a child-parent relationship, even between adults, is a powerful way to ensure that the family members truly feel they belong together.

Conclusion

Whether it is legal, relational, or cultural, permanence can have a huge influence on a person's sense of self, well-being, and the trajectory their lives. Fortunately, we can all take steps to promote permanency for teens and other young people in foster care.* * * *

To view references cited in this and other articles in this issue, click here.

~ Family and Children's Resource Program, UNC-CH School of Social Work ~