Vol. 15, No. 2 • May 2011

Teaching Children to Take Care of Themselves

by Nancy Carter, ILR Associate Director, SaySo Executive Director

As a parent or caregiver of a child or young person, our primary goal is to raise children to be loving, confident, well-rounded, self-sufficient young adults. This is true for any child—adopted, foster, biological, or even those who visit our homes for short periods.

When children who have been abused or neglected enter our homes, it is natural to want to love and protect them. Unfortunately, often we do this by insulating them from opportunities to learn skills that help them take care of themselves. Our best way of loving the young people brought into our care is to teach them that by learning to take care of themselves, they will learn to also love themselves, enjoy their capacity to productively participate in the world, and begin to trust decisions they make as they grow older.

The future is uncertain for young people with foster care experience. So while they are with us, we need to engage them in daily teaching moments. Even the small decisions adults take for granted are important life skill opportunities. When we do this we will feel satisfaction knowing the young people in our homes have increased the number of “tools in their survival kit” to take care of themselves in the real world.

When to Start?

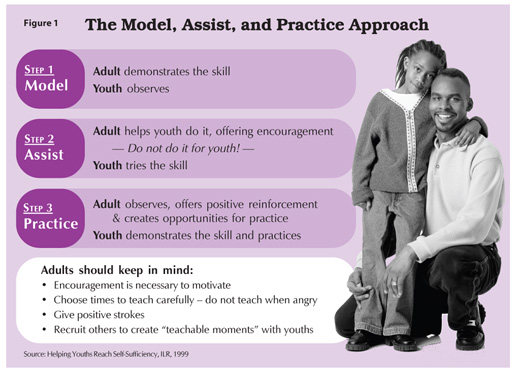

Our responsibility to help young people become self-sufficient begins the moment they are born. Unfortunately, most independent living programs start at age 13 or 16, so there is a misconception that this is when to start teaching young people tools to live in the real world. Federal and state funds are earmarked for youths of this age due to the urgency of their impending transition.Experienced parents, however, will agree that waiting until a child is a teenager to teach life skills means missing out on many “golden moments” when youths are developmentally ready to “do it myself.” When children are developmentally ready, the parent can coach by modeling the skill, assisting the child with the skill, and then finally allowing the child to “do it him/herself,” practicing while the adult provides helpful feedback.

This Model, Assist, Practice method (Figure 1) may happen in one moment or over days/weeks/months, depending on the age and abilities of the child. Parents are cautioned not to assume that because a child is 10 years old, he or she should be capable of performing skills at the same level as most other 10 year olds. Each young person will be at different developmental stages based on the traumas and setbacks they have experienced. This is in no way a reflection of the young person’s ability to learn, so remember to be patient as you become acquainted with the inherent skills and strengths of the children in your home.

Life Skills: A Developmental Approach

Developmentally, children of all ages can learn life skills. The challenge for the parent is to determine what the young person can manage and still be motivated to learn.For instance, when faced with growing piles of laundry, parents should see this as an opportunity to engage their children in the process. Yes, it may be easier and faster to “do it yourself,” but in the long run, teaching skills like sorting, not overloading the washing machine, temperature of water, etc., will go a long way towards helping young people build increased capacity to do their laundry independently.

Consider “playtime” as an opportunity for a toddler to sort the colored clothes from the whites, the towels and bed sheets from the clothes, etc. Once the appropriate piles are made, toddlers can bring the items to your pre-teen to place them in the washing machine, who will then receive some instruction from you regarding amount of detergent, temperature of water, and so on. In some cases, an older youth in the home who has mastered doing their laundry can assist the younger ones.

In the profession of life skills education, it is common knowledge that when youths teach skills they retain that skill at a higher level (Project Stepping Out, Baltimore County DSS, 1985.) Therefore, whenever possible, invite youths with demonstrated skills to teach those skills to other children in the home.

Pay particular attention to how the children respond to your direction. If they grasp the instructions quickly, proceed with the next step. If the young person seems confused, repeat and demonstrate the skill, breaking it into even smaller, concrete steps. Do not forget to Model, Assist, and allow youths to Practice. Parents often need to relinquish some control in order for youths to feel like they can control things in their life, even if it is just the laundry, cooking, hygiene, and so on.

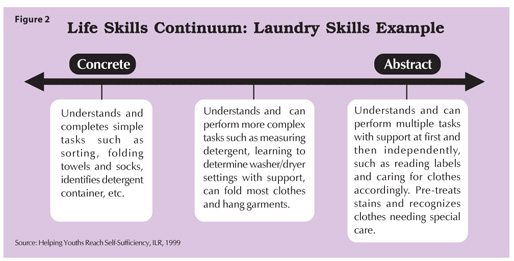

This developmental approach to life skills is based on the idea that anyone at any age can learn something about the skill. The job of the parent or adult in charge is finding that place on the “concrete” to “abstract” continuum (Figure 2) where a young person has the ability to start learning.

Although every skill can be placed on this continuum, do not assume a young person with an abstract level of understanding in the area of cooking will have a similar understanding in the area of work experience. Often the young person’s level of understanding corresponds with the amount of exposure they have had related to the area.

Figure 2 provides an illustration of how the laundry skills continuum can be broken down into smaller, developmental steps. At one end of the continuum, a child is very concrete and smaller steps are needed for the child to understand what to do. This child may even need pictures on a poster to illustrate the appropriate steps to clean their bedroom. Statements such as “go clean your room” are too abstract and a child’s reaction to not understanding the task may range from complete avoidance to anger.

At the other end of the continuum, abstract thinking is achieved. An example is a young person who knows (or has learned from experience) that if they wash their red clothes with white clothes, they will end up with a basket of pink clothes. They also can learn more advanced techniques such as determining dry cleaning needs, removing tough stains, understanding label instructions, etc. Most adults function at the abstract level, so it is natural for them to give verbal instructions to children at an abstract level.

Again, the challenge for the adult is to reduce their instruction /demonstration to more concrete tasks to enable the young person, who may be at any point of the continuum, to achieve some success in learning the skill. Parents and caregivers must always remember that even if the young person does not learn the entire continuum of a skill, consistent exposure and practice with the specific tasks will provide increased confidence.

Of course, parental feedback is also important; it accompanies the Practice step of our teaching model. Be as specific and positive as possible, but not phony. Global statements like “good job” can mean anything or nothing. If you can be specific, it adds credibility to your feedback. The following comments are specific to small tasks: “You added just the right amount of detergent for this load” and “Great job, you remembered the dryer sheet before I reminded you.”

Skills to Focus on

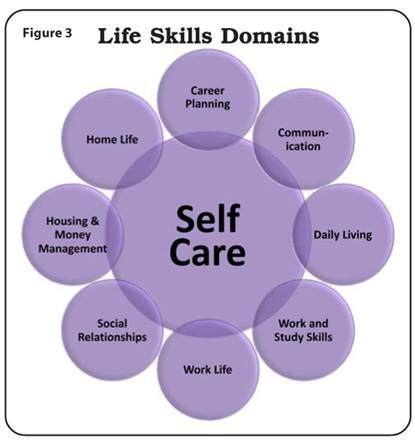

Although laundry skills were used in the example, life skills include both tangible and intangible skills. Tangible skills include activities that are easily seen, touched, and measured such as cooking, laundry, and money management. Intangible skills include those that are more internalized and build over time, such as decision-making, time management, and socialization. Both types of skills are necessary to make a successful transition to the adult world. That’s why it is so important to start exposing youths to a range of skills at an early age and allow them to practice, practice, and practice even more.According to the Ansell-Casey Life Skills Assessment (ACLSA), nine domains are considered important to achieve self-sufficiency. The ACLSA is an assessment approved in North Carolina to determine goals for young people to reach self-sufficiency. The ACLSA suggests beginning these assessments at age 8.

The domains and some examples of each include the following:

- Career Planning: what are youths’ interests and how do those connect to a career plan?

- Communication: emotional health, understands strengths and needs, respectful

- Daily Living: nutrition, meal preparation, leisure time, legal issues

- Home Life: clothing care, home safety

- Housing and Money Management: saving, credit, budgeting, housing, transportation

- Self Care: hygiene, health, sexuality, drugs and other substances

- Social Relationships: cultural, inter-personal, support systems, conflict management

- Work Life: employment search, applications, resume, maintain employ-ment, etiquette

- Work and Study Skills: decision-making, study techniques, how to use the Internet

As Figure 3 shows, some domain goals overlap with other domains—self-care/self-sufficiency skills are interrelated.

It should also be noted that a young person will normally achieve varying levels of competency for each of the domains. Therefore, each domain should be evaluated independently. Assessments can be completed free online at www.caseylifeskills.org.

Programs in every state are beginning to evaluate how well young people are being prepared to be self-sufficient. Through the National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD) and North Carolina’s LINKS program, young people in foster care in our state are now being evaluated through NYTD at age 17 and then again at ages 19 and 21. The areas being assessed include all the LINKS outcomes (listed below), which research has proven to be key for transitional youths (*indicates an area identified by the NYTD):

- Sufficient economic resources*

- Safe and stable housing*

- Attain academic and vocational goals*

- Sense of connectedness outside the social service system*

- Avoid illegal/high-risk behaviors*

- Postpone parenting

- Access to physical and mental health*

Visit http://www.ncdhhs.gov/dss/links/ for more information about the LINKS program and policies. Visit http://www.saysoinc.org to view a presentation about NYTD.

The home and community are the best settings for exposing youths to life skills and giving them a chance to learn and practice them. Parents, guardians, and caregivers (including respite foster parents) are in a perfect position to help expand the “tools in a young person’s survival kit.”

Try not to worry about mistakes they will make. Everyone has a “pink clothes” story. Mistakes are often the best way to learn what works most effectively.

Allowing young people to teach you some skills, such as how to program the remote control or your new cell phone, may help create a cooperative environment of teaching and sharing in your home. One of the best ways to see that you are helping youths reach self-sufficiency is to allow youths to practice those skills and watch them improve. Also, encourage other parents to support life skills learning and practice in their homes as well.

As a community we can build a generation of young people who are better prepared to take care of themselves and care for our world.

For more about life skills education or to contact Nancy Carter, visit www.ilrinc.com.

Copyright � 2011 Jordan Institute for Families